| |||||||

| Search Forums |

| Advanced Search |

| Go to Page... |

|

| Search this Thread |  32,323 views |

| | #1 |

| BHPian Join Date: Jun 2021 Location: Bangalore

Posts: 28

Thanked: 470 Times

| 10,237 km: Bangalore to Arunachal in a Thar “Madam, I don’t know what has happened. There were so many butterflies yesterday. And normally, the birds are out by now, looking for fish.” We were walking on the banks of the Nordhiang, skirting the impenetrable forest cover that looked forbidding up close, no trail visible in its undergrowth. The winter sun was beating down on our heads. It had already been two hours since a local villager had rowed us across the snow-fed river. I wasn’t sure if our guide at the Namdapha National Park and Tiger Reserve was lying to comfort us for not seeing anything more exotic than a pied kingfisher diving unsuccessfully for breakfast. Tourists, having spent money and time, which is also money, get peeved at merely hearing, not seeing, the promised animals and birds. They berate the animals as ingrates for not living their lives in public, ready to be captured with Canons and persistence for walls in the meta-verse. For us to have driven 3,500 km to East Arunachal, home in Bangalore as far away as Shanghai, he probably thought we would expect every creature to line up for inspection and portraits. It was his lucky day though. People like me, a heady mix of the unemployed, the impecunious and the lazy, are few and far in between and ridiculously easy to please. Just the thought of being the only two tourists in that forest that day was enough for us to give out sighs of contentment every so often. “Look up!” A bird flew leisurely over us and soon disappeared into the forest. The guide (whose name I unfortunately do not remember) turned to us. He was looking stunned. We had disturbed a white-bellied heron, one of fewer than 10 in India, all in Namdapha, one of an estimated 100-400 left, marked for extinction in a world where its natural habitat of fast-flowing rivers running through remote forests has already lost its worth. A 2021 study by the Zoological Survey of India and Bombay Natural History Society uncovered the truth behind its dwindling numbers. Its love for solitude, unlike predilections for communal living of other river birds, is to blame; it didn’t find out about new hunting grounds and now finds itself trapped in the 2,000 sq km of Namdapha. How long does it have? I do not have a photograph of that moment. Or of many such others from the 34 days and 10,237 kilometres spent on the road, from Bangalore to Arunachal and back. I wish I did. But then, perhaps social media has made us forget it is enough to be on journeys that challenge us and to live to tell tales of the wonder we feel at hearing hidden worlds we could never see without causing their destruction. This is the tale of one such journey. One to overshadow it might take a while. WHEN Medusa, my beautiful grey Mahindra Thar, came into my life in June 2021, I knew I would head towards the North East India soon. It would be a perfect way to flip around the not-exactly-a-good-year I had been having, what with the pandemic having extracted its price and changing my relationship status back to single, absolutely and irrevocably unwilling to mingle. Bhutan had been top of the mind recall, but a chance remark across a friend’s lunch table suddenly brought Arunachal Pradesh into focus. The state is celebrating 50 years of its formation in 2022 and Sanjay Dutt can be found smiling in promotional videos as the new brand ambassador. In a country mad about stars, the choice is a testament to the value the state places in its wildlife. It also perhaps sends the neighbouring thug the usual weak, albeit belligerent, message. Incidentally, that neighbouring thug is the only reason mass media mentions the state. Declaring Chinese names for territories it claims and kidnapping a teenager hunting around the disputed border (after being released, he was quoted saying he wishes to join the army — the Indian one thankfully) provide valid circumstances for the mainland to indulge in chest-beating, vote-winning, nationalistic rhetoric. Such stories, while not exactly beams of happiness and sunshine, get a few more among the billion plus curious enough to register Arunachal Pradesh as a state. The state administration has been making efforts in the recent years to get tourists. And for once, thought is being given to income generation for indigenous people before plundering their land. A few gregarious souls, delighted with an alternative to farming and building roads in bucolic isolation, have already availed of subsidies to start homestays and are welcoming Bengalis and Assamese on weekend drives made popular during the pandemic. Biker-vloggers have been hard at work for some time now. How can all roads be dangerous, I scoffed when watching the umpteenth GoPro footage. It must be wizardry of camera angles. The first internet search throws up the government site with lists of places and their anaemic descriptions. It does not even yield top tips for visiting Sela Pass and Tawang for the snow and about the annual Ziro Music Festival held among green rice fields surrounded by mountains, two of the more known places. And when the algorithm eventually leads to the few posts by local residents in other towns in the state, they really don’t make an impression. The distance is not merely physical. I mean, what is Walong and Wakro and West Kameng? Blogs and articles can be found only by serendipity. The Team BHP site has a few travelogues of people covering North East in a short sweep. But in spite of all the information I scrounged out, I felt more familiar with the concept of an Australian Bush, which I am yet to visit, than with Arunachal Pradesh. Write-ups of a convoy-style Thar Trans Arunchal trip organised by Mahindra early last year ultimately became my reference point. Different accounts by invited journalists gave the idea that one could traverse from the east to the west of the state along the NH13. Of course, that convoy had a support crew, not to mention support vehicles, to make and dismantle camps at will. I would need to depend on homestays and dodgy highway hotels. After a while, I gave up trying to ascertain destinations and putting them in order. Time estimates with accompanying description of chaos on the road were wildly varying, for no apparent reason. It’s in India, right, and I would be in a Thar, I thought. I could do a beating retreat to the last place with hot water. With a go-with-the-flow itinerary in mind, the “when” was easy. December has acceptable levels of cold and rain, though one cannot count on such things in these days of a post-climate-change world. Nevertheless, it would certainly be better than the months sure to bring landslides, if the newspaper articles were to be believed. Prepared to go alone, I started talking about the plan to my family and friends. Pater said, “Alone? To Arunachal?” Unexpectedly, some friends expressed interest and I started pondering. This was likely to take a month, 10 days just going to Guwahati and back because I wasn’t keen on 15+ hours of daily driving. This would be a marathon, not a sprint. And the Thar, which I love to bits for its many things, well, it ain’t superfast. As I thought more, I began to realise the mammoth undertaking I had my heart set on. Having done only one 700-kilometre journey alone at the time in the Thar, a co-driver would be invaluable. Ultimately, the friend with no time constraints, a far more experienced driver, the recent ex-partner (yes, friends too had exclaimed in fascinated horror) became the chosen one. The decision might have been aided by another friend screeching in my ear, “Arunachal?! Ditch the women and take the man!” So, Ray and I packed our bags and were off on 1 December 2021. Last edited by Sonali Singh : 16th May 2022 at 14:07. Reason: Editing the travelogue |

| |  (70)

Thanks (70)

Thanks

|

| The following 70 BHPians Thank Sonali Singh for this useful post: | @og_adi, ABHI_1512, Alpha8118, anoopelias, Arreyosambha, Axe77, A_Abhiraam, Bibendum90949, blackwasp, Blue Thunder, carrot_eater, Contrapunto, CrAzY dRiVeR, curiousElf, dailydriver, deepfusion, denzdm, DogNDamsel12, Dr.AD, Excommunicado, FAIAAA, Fuldagap, glovins2004, GTO, gunin, gururajrv, GutsyGibbon, g_sanjib, h0rnokplease, haisaikat, hmansari, Ironhide, johy, kannan666, KK_HakunaMatata, Leoshashi, luvDriving, MercFan, One, ph03n!x, planet_rocker, pratyaksh, Pyrotek, Red Liner, Researcher, Rigid Rotor, rj22, Roy.S, rphukan, sainyamk95, Samba, shashanka, shipnil, Siddy_1998, sierrabravo98, SoupRaw, spdfreak, SR-71, SS-Traveller, subie_socal, SVK Rider, Taha Mir, Turbanator, udainxs, UMe, V.Narayan, venki.bala, Vishal.R, WhiteSierra, zurura023 |

| |

| | #2 |

| BHPian Join Date: Jun 2021 Location: Bangalore

Posts: 28

Thanked: 470 Times

| Re: Arunachal: A Siren Call into the Unknown START was delayed, a prognosis of days to come. More items were seeming more indispensable by the minute. After essentials — a duffel bag of clothes, shoes and toiletries each, a tent bag and off-roading recovery gear — had gone in, so did four coconuts from the garden, a copy of Ulysses, an icebox, left-over raisins, toilet rolls, soy milk, a hairdryer…no, don’t roll your eyes. Initial excitement waned after crossing the Karnataka border. Long stretches of dusty roads flanked by rocky hills with temples on top, highway restaurants with indifferent food, and toll bridges were all we had. The occasional small town or village cut the speed but momentarily. Vignettes of rural India going about its life — tiny tempos and large tractors carrying grains, cauliflowers and shiny plastic chairs, uniformed students walking to school, women in shiny saris travelling with men in white — soon lost their charm. Diesel prices provided the only gawk-worthy entertainment. Peace was temporarily shattered right at the beginning, just before Tirupati, by a stone chipping the windscreen. I pouted for an hour and blamed the co-driver, secretly thankful I was not behind the wheel at the time. A quick search on the Team-BHP site about lorries and their flying pebbles lead me to an astonishing thread on such happenings to others in the same stretch. Parts with choke points felt like Temple Run; thankfully, demon monkeys were not at hand to attack us if we made a wrong move. First it was the long-haulers lined for scores of kilometres, as multitudes worked around the clock to re-build the Chennai-Kolkata highway swept away by Andhra floods and traffic police laboured to manoeuvre smaller vehicles through the chaos. Then it was the bridge over Godavari. Suspended over the longest Peninsular river in South India, I dwelled on why it had taken me three decades to see what I had read about in school. Cyclone Jawad gave us a half-hearted chase from the beautiful Chilika. And just before Kolkata, Google Maps trapped us, in quite the Abhimanyu-in-chakravyuh style, with a promise of a bridge that turned out to be made of bamboo. We drove desperately for an hour and half to escape the Bengali countryside, replete with startled villagers and slow-motion cyclists who didn’t respond to the word “highway” (hot tip: “main road” works). We were also unwittingly and unwillingly lured into an off-roading experience with the trucks among the moon craters of Moregram, a forgotten stretch of NH14 as close to Mad Max:Fury Road as we would get in our lifetime. After that, the notorious, daily vehicular stand-off at Farakka Barrage seemed like a deserved period of rest. Melas with their maut ka kuan set-ups, Bollywood tunes, and chaat vendors added to the bustle of small-town life passing by us, even if in the light of green and red bulbs, they resemble hunting grounds for serial killers to Netflix-addled brains. Hold on reality becomes tenuous after interminable hours on the highway, cocooned against the elements. The mind wanders. What were those mysterious, colossal industrial parts that look like they belong to power plants, but don’t? They dwarfed everything in their paths. Were those really mud and grass huts? Highways in Orissa are on their way to being like Andhra Pradesh’s, broad, bland, all trees massacred at the holy grail of driving at an unforgiving pace. But they haven’t yet been stripped off their West Bengal influence, where everybody and their goats, chickens and children lead full lives. Was that…yes, a woman was really squatting and beating clothes with a laundry bat on the side of a national highway. And that 2-days delivery you and I are now used to, calling customer service in fury if those silicon storage bags are not delivered at the speed promised while taking Rs 1,499 off our hands, what does that do to the highways? Do we blame the government for that too? The trucker’s life is spent in a cabin heated by an unrelenting sun and then snaking through the night on roads lit only by others like him, ants with headlights. He (no demand for gender equality here) eats in the shade of a tree if he can find it, or under the dim, white light of a bulb at a dhaba, which he always does.He perhaps finds solace in fleeting conversations at the chai shop and in the warmth of a hug that can be bought in ghettos that come up to service all like him, and perhaps his wife and son understand. Would I? Highway hotels provided comic relief. One must not say, when travelling with a man one is not married to, ”We need a room for the night.” And one cannot expect profit margins to accommodate detergent supplies. But mornings make these buildings, however dismal they had seemed when checking in the previous evenings, appear cheerful, vaguely reminiscent of Amol Palekar and Sanjeev Kumar films, a happy small town vibe in their innocent shabbiness. The staff serves with the pride of a white collar job in a largely agrarian setting, closest to the air of nirvana that can come only of a government job. And after the inevitably greasy puri-aloo and omelette-bread breakfasts, one feels fortified for yet another day on the road. Once, we received a surprise recommendation with the mandatory safe-journey goodbyes. We would be passing within sneezing distance of Shantiniketan, and of course we wanted a photograph of the tree under which Tagore had probably dozed off in the middle of writing “Where the mind is without fear”. The list of tactical strategies to avoid debacles grew longer. Watch the blue and white signs. Follow the trucks. No, follow the locals. Stick to wider lines on the map. Except when there are none. Then throw up your hands and follow the yellow, brick road. The air changed after passing the chicken neck of Siliguri and the Coronation Bridge. It was hilly climbs and tea gardens, and then the roads widened through the rest of West Bengal, and just like that, trailing a tempo with two young men checking their phones, blue skies and sunshine and puffy clouds in surround-view, we were in the North East, passing road signs that proclaimed Bhutan was 50 kilometres to the left. We stopped for a day in Guwahati to use the washing machine of one of Ray’s classmates from the distant past. And then for another to see the stunning Kaziranga National Park with two-thirds of the world’s rhinoceros population and other assorted beings, the Siberians blending in with the locals, all in a surreal display amidst the tall, elephant grass and the winter morning fog. Soon it was the home stretch. And eight days after leaving Bangalore, at dusk, we crossed the border at Dirak Gate in the eastern part of the state, with no one interested in our Inner Line Permits. We had made it to Arunachal Pradesh, the land of the dawn-lit mountains. At Shantiniketan  Mooncraters of Moregram Entering Assam   At Kaziranga Entering Arunachal  Last edited by Aditya : 18th May 2022 at 09:57. Reason: Rule #11 |

| |  (38)

Thanks (38)

Thanks

|

| The following 38 BHPians Thank Sonali Singh for this useful post: | AROO7, Axe77, Bibendum90949, blackwasp, curiousElf, dailydriver, deepfusion, Dr.AD, FAIAAA, GTO, gunin, g_sanjib, h0rnokplease, haisaikat, hmansari, Ironhide, JoseVijay, KK_HakunaMatata, livetodrive, luvDriving, ph03n!x, Pyrotek, R-Six, Ravi Parwan, Red Liner, Researcher, Rigid Rotor, rj22, Roy.S, Samba, shipnil, Siddy_1998, sierrabravo98, SS-Traveller, subie_socal, SVK Rider, UMe, whitewing |

| | #3 |

| BHPian Join Date: Jun 2021 Location: Bangalore

Posts: 28

Thanked: 470 Times

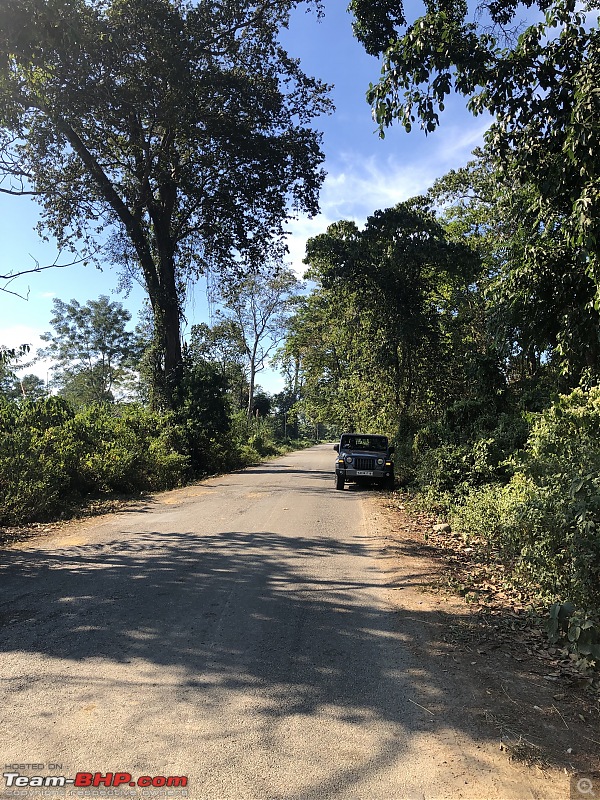

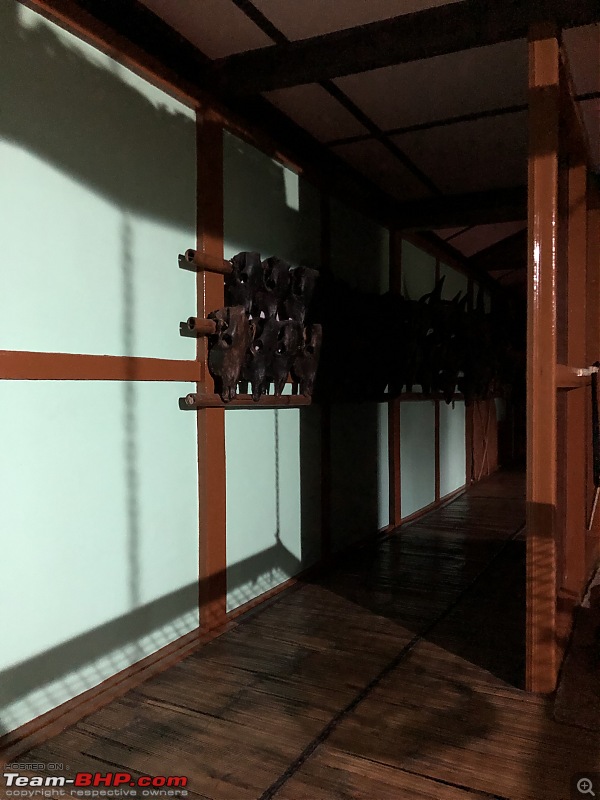

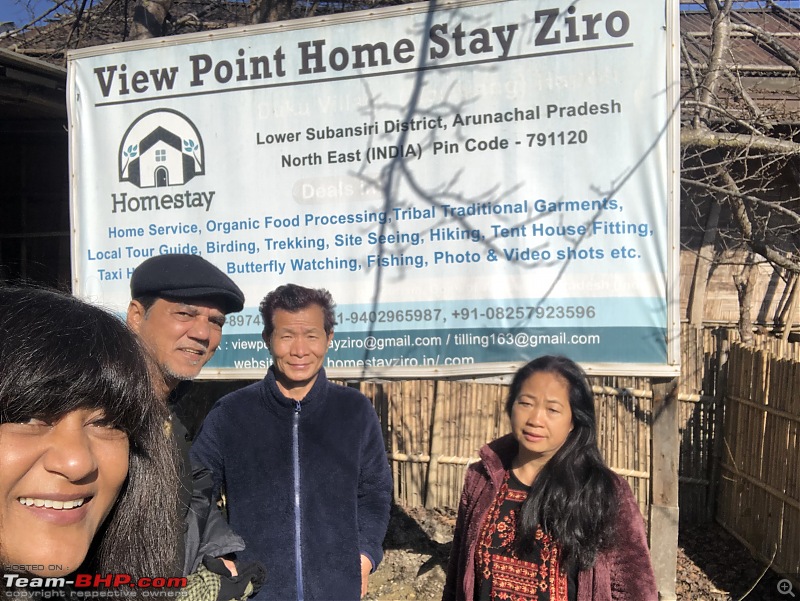

| Re: Arunachal: A Siren Call into the Unknown AGE has crept up slowly, accelerated during these last two years of the pandemic. With it has not come wisdom. But there is a realisation that connections from the growing-up days, however fleeting, are not temporary. Or perhaps it’s nostalgia, which rarely used to plague me earlier. Whatever be the reason, I found and messaged Jarpum. I think we might have spoken once when in XLRI many moons ago, or perhaps, never. I wanted to meet him after all these years, because I had heard he had gone back to his state to work for the community in Arunachal. I was delighted when he called back. Of course he remembered me, he said. He was unfortunately in Delhi at the time but insisted I keep him posted based on our whereabouts, as he could help with current information on“road cutting” underway, a combination of words now evocative of Arunachal, like“fooding and lodging”. I told him we planned to book places for night halts on the fly and he helped get us started. That’s how we ended up at Khemsaa Homestay on our first evening in the state. Towns (the last census didn’t uncover cities) in Arunachal generally have a handful of hotels and a government-run Yatri Niwas, most of which have running water, Western toilets and geysers, the newer among them even air conditioning. Apart from the capital, a few with a steady supply of travellers, like Tawang and Bomdila, will offer choice. Menus show love for the ubiquitous north Indian and Indian Chinese, with a small section of watered-down versions of local dishes. Resorts, where they can be found, often are small campuses with traditional huts, better maintained than the hotels. In villages and smaller towns, one can book from a network of Inspection bungalows, either of the forest department or PWD, and circuit houses. Though bookings can be cancelled if a government official happens to be in town. To the feel the heart beat of Arunachal, however, one has to choose homestays. All owners host travellers in their own homes, most not yet expanded with additional rooms, manage the communication and the maintenance and the cleaning and the cooking mostly by themselves. With 26 tribes in Arunachal of more than 5,000 people (there are a total of 110 tribes and sub-tribes) spread across, homestays reflect each of their unique cultures. Each tribe has its own language, and with no common thread running through the many in the state, Hindi is spoken throughout. One can hear stories about their people over a constant supply of lal chaa, and upon request, eat what they eat, cooked with love and with ingredients grown in their farms or kitchen gardens. The Khemsaa homestay in Lathao, a village just ahead of Namsai, is run by a Tai Khamti family, the only tribe with a script accompanying their language. From the front, with the guest rooms on the ground floor and the family rooms on the first, it looks like any other house. But there is a traditional wood and bamboo house at its back, which has three rooms: a drawing room, a dining room and a kitchen. No family guest ever uses the drawing room. The dining room, not a common feature in homes here, is for people like us, who are new in the state or wish to maintain our habits from back home. It is the Arunachali kitchen, where, unlike our apartments and houses in the cities, lives are lived. A wood fire burning in the centre, aluminium kettle placed on an iron structure over it, is the fulcrum of social interactions. One pulls in a low, cane muddah from among the many around to sit and get warmed. While one shares how the day went, another is transferring hot water into a tea pot to make lal chaa. The kitchen stove is placed in another part of the room, but tomatoes, chillies and dried, often fermented, fish, and sometimes even red potatoes are roasted in the fire. Cooking is not an activity to hide or display, and definitely not contemplative. This entire arrangement of the traditional kitchen cannot be placed in a brick and mortar room; the fire needs the ventilation of bamboo and wood floorings and walls and ceilings with a chimney. Thankfully, it isn’t going anywhere for some time. Winters are cold and electricity supply is unreliable. Kinchowa, her mother and two other women in the kitchen quickly whipped up a delicious meal. The food was simple and delicious, in a template we were to become familiar with: sticky rice; potatoes, sometimes with turmeric; chutney, often with fermented fish; and greens and other vegetables, flavoured with ginger and bamboo shoot. Everything was boiled or steamed or roasted. The family is Buddhist and therefore vegetarian but broiler chicken (making inroads only now; country chicken is still preferred) had been made for Ray. The mother is an old biddy, with her cloth bag full of what-nots slung along her shoulder. She could not speak Hindi but understood it and was prompting Kinchowa to ask us questions. She heard my answers with twinkling eyes, taking breaks to help in preparing the food. Awake by 4am, sometimes even at 3am, she goes walking into the fields to meet her friends. They sit and chat, and when Kinchowa wakes up, get lal chaa. They all are generally in their rooms by 7pm, likely the reason Kinchowa’s relative in Namsai was not keen to host us, once she realised we would arrive not earlier than six in the evening. We got our first look at Arunanchal the next day. Destinations and their order and directions were discussed with the family, as was the Thar; they had booked one too and the mother made me open all doors and peeked inside and nodded her approval. Our initial plan was to head straight to Dong village. But Namdapha appeared thrillingly close on the map. Ray had forgotten travelling with me meant heeding random inspirations and pouted at the change of plan. Back on the highway, a couple of men milling around the mini-ATM, which seemed to be on the desk of a shop, confidently pointed us in the right direction. They exclaimed at our plan of traversing the state but reassured us on the pristine condition of the roads. I started wondering with delight, and a slight disappointment, if the apocryphal Arunachal roads had been completed in the past months. We had encountered nothing but beautiful tarmac. First impressions? Where are the people, I asked the co-driver, as we drove through a desi Constable painting? They must be in the fields, he said. But we are driving through fields and I can see no one, I replied. Shrugs. There was evidence of human activity but no humans, for long stretches. In the distance, just beyond the fields, one could see forests, and soon, hills. We passed by scattered houses, all at a distance away from the highway, and small shops with reams of sachets of shampoos, chips and shrimp paste. Zooming past a University made us feel more certain of still being part of civilisation, although it was not exactly teeming with activity, or even students, like we are used to in the mainland. “In the mainland”? Where did that come from? The North East is part of the main landmass of India. Even then, in our last visit to the North East, Meghalaya and its network of living roots bridges and its women in a Khasi household occupying the centre of a home while men skulked in the periphery had felt like a different country. Arunachal takes it up a level. It feels like a world floating by itself, untouched by the seven sins. Miao, a couple of hours away from Lathao, was bustling with activity. But the sense of isolation came back on the single lane road beyond, with the Nordhiang river to our left, the wall of the hill to our right. Vegetation was getting denser, darker. Around a couple of villages on the way, children were on their way back from school, playing like the road was their garden. Well, it could have been, for Cubbon Park when closed for the evening has more people. Soon, we were at the boom barrier of the reserve. A game of carrom underway was paused and one of the men opened a register and asked us for the permit. What, we had to get a permit, from where? From Miao, at the Namdapha Tiger Reserve office. Wait, what? One cannot phone? No, there was no phone. Needless to say, there was no mobile signal either. And can we stay in the forest lodge? Ah, the register of bookings is at the same office, is it? Right. Back we went, to the office in question, where a few people sat on the benches, desultorily chatting, waiting for lunch hour, in a standard-issue, high-ceiling old government building. I was directed to a small corner room on the ground floor and went through a curtained doorway. A large non-Arunachali man was sitting behind a desk full of papers, surrounded by files, and diagonally across from the smaller table with a woman typing away on an ancient computer. Yes, madam? I introduced myself and explained the situation. Ah, you did not seek the permit in advance? No problem, please write an application to me. I would need copies of your Aadhar cards. Of course, though I have only the originals, I am afraid. He tinkled a bell and a young man, a local, came in. He soon scuttled away to find some paper and pen and a sample application. In the meanwhile, I asked if we could stay there too. Madam, you wish to stay? He took out a register and started pouring over columns, running his fingers along. Yes, you can be accommodated. How many of you are here? Two and we need one room. Can we book a night’s stay and extend by another if we like it? He looked over his spectacles, shut his eyes, took a deep breath and sat back on his chair. Madam, you must understand, you have to make the booking here. Else, there is no way for me to know what rooms are occupied in the forest lodge. What if tomorrow there is someone like you who wants to stay? It will throw the system off, madam. Please. I reassured him my intentions were anything but. May I book for two days and decide if I want to stay only one day? Yes, that can be done. Excellent. The young man had come in by then with supplies and left them on the table before exiting the room. I completed the application and handed it over to the officer. He went over each word with a pen as a pointing tool. After being satisfied, the young man was called in again and handed the paper. The paper was taken to the desk three feet away in the room and the woman looked at it. She placed it on her desk, continued her typing till the end of the document she was working on and then got up to make copies of the Aadhar cards. Soon, papers made their way back to the officer’s table and I had my permits and bookings. Profuse in my thanks, adding a bow for good measure, I left the office. Well, why not have some lunch before heading back to the jungle? There were no Arunachali food to be had in Miao. The question had thrown all three back in the office. Everyone had shaken their heads. Calls to their friends assured them their information hadn’t yet been outdated. No, everything was either Indian Chinese or Nepalese, momos or noodles, a stereotype brought to life. We ended up at a small hole-in-the-wall with three tables, run by an Army veteran with a gold tooth, sitting in front of Dalai Lama’s photo and watching MMA fights on his mobile. After lunch, we headed back to the forest, not stopping at the one ATM in town with a long queue. Doubt the forest would provide spending opportunities, if the room rent was anything to go by, Ray said. Back at the entrance of Namdapha, we were legitimised as tourists and allowed to enter. In the buffer zone, we would have passed perhaps three vehicles, all carrying supplies for construction or living, and a bike or two with villagers from the settlements inside. After 10-15 kilometres, a lodge emerged in a forest clearing. We were admitted in after the required documents had been checked by staff startled with our presence. With the main lodge under maintenance, we were taken to a small one-storeyed, decaying building with four rooms in a row, each at a different stage of the end of its life. Were there other options, I asked? Yes, in traditional huts overlooking the river. Would madam like to see? Yes. Even they were decaying but, being made of bamboo and wood, and on stilts, they didn’t have that dank odour. No water though, I thought, imagining myself going down to the river bed and carting water up. Mr Gogoi, a dark, bent Assamese man, came up. He is the caterer but ends up as the caretaker of tourists, other staff in the lodge more intent on holding court in the garden in the prettier parts. You should take this but we have to ask the officials, he said. And I will switch on the water pump, he added. The officials in the garden looked shocked at the effrontery of my approaching them directly with the request for change in quarters, but they readily agreed. Finally, we were on the small bench in front of the hut, Medusa behind us, all three looking out at the river and the dense forest cover beyond out. Where were we? Were we really the only two tourists here? The setting sun cast a glow all around, especially on a tractor stealing sand on the other side of the river. Stars came out bright and in full strength. And what was that, if not a glowing Superman shooting across? Satellites! We counted six through the evening, criss-crossing above. Do they have cameras that can zoom in? If yes, then likely their operators were wondering, who are these folks and what do they want and why do the woman and the man heave such contented sighs? Are they ok with water in broken buckets and English toilets without a flush tank? And with the food cooked by Mrs Gogoi, with only eggs, for there weren’t enough people for a full chicken? And that bedsheet, the woman was ok with the bedsheet? I had not realised I would need the Set Up so soon. Anticipating certain nights may be in environments not quite the thing, I had packed a down sleeping bag, a felt throw, a cushion that converts into a quilt and scented candles. Smugly, I put everything in order and we dove inside the temporary cocoon to emerge bright and cheerful the next day. The one trail that leads deeper into the forest to the three camps set up by the tourism department hadn’t been cut this year, but we were told we could walk on the river bed. We meandered around for a few hours in the area and came back excited with our encounters with butterflies, herons and gibbons. After an early lunch, we started retracing our steps to Namsai with the original first destination in mind (retracing is part of life here, off the NH13). With not enough driving time at hand to go significantly beyond — what with an argument only two men can have on who’s fault it was that two cars, both in first gear, on an empty forest road had scraped each other, each adamant the right of way was his incontrovertibly — we chanced on a homestay in Wakro and reached it after dark. Close to Wakro, I shrieked with delight. There was no grand board marking the beginning of the NH 13, the Trans Arunachal Highway, but there it was. At Khemsaa Homestay   On way to Miao  On way to Namdapha  Inside Namdapha      Last edited by Aditya : 18th May 2022 at 09:55. Reason: Rule #11 |

| |  (35)

Thanks (35)

Thanks

|

| The following 35 BHPians Thank Sonali Singh for this useful post: | ABHI_1512, anivy, Axe77, Bibendum90949, blackwasp, dailydriver, DogNDamsel12, Dr.AD, gadadhar, GTO, gunin, g_sanjib, h0rnokplease, haisaikat, hmansari, Ironhide, johy, JoseVijay, KK_HakunaMatata, luvDriving, ph03n!x, Pyrotek, Red Liner, Researcher, Rigid Rotor, Roy.S, Samba, Sayan, shipnil, Siddy_1998, sierrabravo98, subie_socal, SVK Rider, Taha Mir, UMe |

| | #4 |

| BHPian Join Date: Jun 2021 Location: Bangalore

Posts: 28

Thanked: 470 Times

| Re: Arunachal: A Siren Call into the Unknown NINASHI homestay is marked by a signboard and has a large gate. We parked in the grounds around the single storey building and dashed inside, eager to escape the rain and the cold. Ah, the kitchen again! A touring Assamese family based in Mumbai was sitting around the fire. I went looking for Ninashi, who turned out to be a small, diminutive Mishmi woman, in the kitchen cooking up a traditional feast like she had promised on the phone. The dinner here was perhaps the most unfamiliar of the entire journey and I promised I will be back to learn each and every preparation she was willing to share the recipe of. The company that day was unexpected, merry and a welcome change. In the quiet of the morning, with a cup of lal chaa in hand, I explored Ninashi’s homestead. Her children had grown up. Upon hearing from a local official about the homestay scheme, she had taken it up as a challenge. She had initially been discomfitted by strangers in her home but had started liking the conversations and the opportunity to share her life with travellers. Now she was building extra rooms. Everything was wet that day, a decadent green with the overnight rains. Would it be like this throughout the trip? Enter a new place in darkness and discover the landscape after dawn? Ninanshi’s tea garden and other crops were next to gentle hills. A mithun glared at me from his post. He had bellowed all night. A cat meowed for attention, or warmth, as it snuggled into my shawl. The kitchen garden on the other side of the house had provided practically everything on the table the previous evening. Did we have to leave? Breakfast was porridge, the prosaic word unfit for the delicious, steamy concoction of sticky rice, made of three kinds of rice, and whole urad daal. And, Ninashi added, a dash of dried, fermented fish roasted in fire. I bought two kilos of that rice. Before leaving, overwhelmed by the stay, we offered Ninashi a coconut. After a quick photograph, we were back on the road. The act of taking a photograph is strange. Do I take it for social media or as a visual note? How many should I take indiscriminately to ensure I have what I wish to display? For I am never able to capture that feeling, that moment, ever since the digital replaced the film. Phones democratised photography but couldn’t transform the average person into a photographer. In On Photography, Ms Sontag said we appropriate the thing being photographed, we colonise through photography. As tourists, we focus our gaze and change the place and the person permanently. And yet, we like to think we have looked into the soul of a place and now know the authentic, unchanged-over-centuries culture and understand the people in the 3D/2N we pay to stay at a hotel in a part of town chosen for its beauty or proximity to the attraction. In Arunachal, I had the urge to take photographs of the people because they are so different, but for what purpose? I was not studying them or their tribes. I was not going to compose a photo essay. Though in areas with more tourists, the photogenic and the shocking (to the middle-class sensibility, a face tattoo is) were being paid to pose. For my memories, one photo with the homestay owner and staff would have to be adequate. How would I feel if camera-totting Caucasians come into my apartment building and start photographing, pointing and exclaiming every time they saw a woman wearing sari or flowers in the hair, and wonder at men clad in the jeans and t-shirt instead of a version of the lungi? At Ninashi Homestay       Last edited by Aditya : 18th May 2022 at 09:56. Reason: Rule #11 |

| |  (31)

Thanks (31)

Thanks

|

| The following 31 BHPians Thank Sonali Singh for this useful post: | ABHI_1512, Alpha8118, blackwasp, curiousElf, dailydriver, DicKy, DogNDamsel12, Dr.AD, GTO, gunin, h0rnokplease, hmansari, Ironhide, johy, Joscyriac, JoseVijay, KK_HakunaMatata, luvDriving, ph03n!x, Pyrotek, Red Liner, Researcher, Rigid Rotor, Roy.S, Samba, shipnil, Siddy_1998, sierrabravo98, somspaple, subie_socal, Taha Mir |

| | #5 |

| BHPian Join Date: Jun 2021 Location: Bangalore

Posts: 28

Thanked: 470 Times

| Re:Arunachal: A Siren Call into the Unknown THE argumentative Indian loves to visit the border. In history lessons, our country and the armed forces’ deeds are glorified to perfection, a perfect white background to saffron and dark green. The chest puffs up with pride, eyes get misty thinking about martyrs, the national anthem is hummed, and there is a furious, surreptitious internet search for said history to write in photograph captions. Well, who am I to defy the gold standard? Next day, as the intrepid trio moved towards Kaho, there was a sense of anticipation unlike what it had felt to approach Namdapha. Myanmar had nothing on the fiery dragon we were about to glimpse. Nationalism had to wait though. The NH13 had gotten slightly broader and a petrol pump Ninashi had promised existed was not on our way. And suddenly we were in the Eastern Himalayas. The Lohit, to be our companion till the border and back over the next two days, came into view. Like all rivers in Arunachal, the Lohit is also snow-fed and snow-green. Gushing on jagged rocks to our right, its waters tempered under the bridge and the river broadened towards the plains on our left. The cloudy, gloomy day did nothing to dull its underlying ferocity. Standing on that bridge, cold wind in the hair (the kind Spotify promises its music is best heard with for cheapskates — ahem — who refuse to pay subscription), the much-maligned cobwebs in my city-dweller brain were banished. Parshuram Kund was somewhere there. I don’t have much to say about religion but I have found myself at pilgrimage sites like Kedarnath, the Maha Kumbh and Manikarnika Ghat, curious about what makes them tick and have been amazed at the sense of faith even an atheistically agnostic like me can feel in the air. But here, with only two cars other than ours right now, the mind recoiled at the grotesque vision of the Lohit Bridge teeming with sadhus and sinners taking selfies after washing away their grime. Till now, the road had been as much of a marvel as the river. Why had everyone said we would need a night halt before hitting Kaho? May be we would not make it to Kaho, the village at the border, but Walong, the closest place with homestays, was just 200 kms and here we had already done 23 in no time at all, time out for jaw drops at the Lohit notwithstanding. As the road veered off the NH13 for our first detour into a valley in Arunachal, our collective complacency started getting dents. The flanking forests, the river and the often not even two-lane roads in between, and, oh god, the mountain whose face had been clawed by JCBs, took their turns to instil doubt. Those apocryphal Arunachal roads? Well, not quite apocryphal after all. Soon Medusa was the only one left with arrogant nonchalance. Army posts looked at us with mild suspicion. Who are they? Tourists? We certainly didn’t passed any on this route. We took a break at a point overlooking at the valley, clouds like cotton in front of us. As I was making tea (tea bag tea is tea, when faced with no tea), I was asking myself for the second day in a row, where are we? Is this too part of India, this wild, green frontier with a bit of tarmac-y ribbon that seemed to have been magically dropped in the middle of mountains. And that rainy day, anything below a Sumo was being sucked into the quicksand-ish slush. A brave, or desperate, Maruti 800 trying an incline could barely move two feet. Soon, visibility dropped to a few scores of metres, as we were enveloped by a dense mist and plants on steroids. What if we chance on a truck, I thought? We didn’t. The three we heard in the vicinity remained ahead until the road became broad enough for a short stretch to overtake them. Or a convoy, I asked the co-driver tremulously, not counting on continued good luck? Well, it seems one squeezes along the edge of the mountain, just before the road bends, and stops. The lead truck rumbling along will hopefully see the car and, taking pity on the driver’s bulging eyes, open mouth and silent scream, swerve gently so as to not knock it over, thus setting an example for the 23 vehicles behind. We even had a jeep stop and roll down the windows. Were we in trouble, was Ray a Chinese agent, did I look like one, I thought wildly? You guys are coming from Karnataka, saw your number plate? I am Major A-and-B and I am from Mangalore, soo nice to see you guys. Ah, a homesick man, thrilled to see people who had been close to his hamlet recently. If after a few days, we were feeling like we were in a parallel universe, for him it would be akin to being stuck on a planet in that universe. All very Dr Who. It had taken us four hours to cover 88 km to get close to Hayuliang. With clouds working hard to prevent consistent navigational support, we had shot past Khupa. I checked the map. Yes, we had to retrace a kilometre and go off the state highway. The village with less than 400 people was known to all as the last petrol pump on this stretch. The previous one was 100 km back (shudder); the next one was in China, where a warm welcome was suspect. Medusa, still happy, rocked away again and deposited us on a road attached to its tarmac. The village didn’t have a square. Like towns in Westerns, it had a small stretch of a road, flanked by a few shops and restaurants. It had a bakery too. The woman behind the counter with a phone held in between her ear and shoulder nodded a yes to my question of whether the bread came from close-by, stretching an arm in a general direction to her left. The petrol pump attendants were from Rajasthan. How did you guys reach here? From the sounds of it, the Rajasthani owner had married a local and got a license and happily lived ever after. You won’t be able to make it to Walong in this weather. Well? We can call the lodge next door and ask Dadu if he can accommodate you. Why don’t you go and have lunch? Ok. We strolled down to the closest hole-in-the-wall, the proprietress thrilled to give us bread and omelette and at the opportunity to satisfy her curiosity about us. Most simply fill up on fuel and leave. It was around 4pm, already getting dark, when we were told we could go across. Dadu was the caretaker for the lodge, a building next to the petrol pump, and he held up a torch as he lead us to the room he had opened for us. There was no one else staying. All electricity in the area, he said, gets sucked up by the JCBs at work on the state highway, but we receive some in the mornings. He got us buckets of cold water. Later he called us to the dining room for daal - bhaat, chicken and sabzi he had cooked. Back in the room, I realised we had good internet and caught up with a Grey’s Anatomy episode, bundled up in the cold, in the light of our solar lanterns hanging from the posts of the bed on an another pitch black night. And woke up next morning to snow in the distant mountain peaks. Gnarls lasted only till Hayuliang, a major army base and town, and then the road opened up, or rather, smoothened up. This is why the Chinese went back in 1962 after encroaching in and why successive governments since then have not troubled the Border Road Organisation (BRO), I thought. Mountains form a natural border, and roads around Hayuliang act as moats with crocodiles around castles. The Lohit below thrashed past in the opposite direction; we got a closer look at its fury from a bridge ahead. Of course, there were consequences to hearing all that gushing sound, especially after having water and tea. On the edge of the bridge to Hawai, there were some uninhabited small structures. Where are the people? That question had become a litany, even as I searched for a home to request access to a toilet. Oh there, two people in a tiny shop. No, they didn’t have a toilet. Another two came ambling along, who recognised KA number plates; they had worked in Bangalore for a few years. As they were chatting with Ray, I dashed into a structure he had indicated with his hand and realised it was indeed a toilet. How does he know such things? I was feeling grateful I didn’t have to half-undress in front of four-legged creatures. Yesterday, despairing at lack of villages or even huts along the highway, I had to make do with a couple of bushes accommodating enough to be growing in a manner to provide a modicum of modesty. But the business had to be done with peripatetic mithuns pausing their chewing to look balefully at me. They appear with more regularity than humans, often solitary creatures ambling along, forever chewing. Part-domesticated, part-wild, they are branded and not put to work. Only on occasions of marriages and such are a few sacrificed and eaten, the skulls cleaned and proudly displayed in the house, or on the outside wall, the increasing collection a vivid show of wealth for families. We had seen the first at Ninashi’s. The road had become winding and smooth, with only a couple of recalcitrant sections under siege, full-scale operations underway to tame them. With unreliable, if not missing, phone and internet signals, walkie-talkies are used to communicate across ends to co-ordinate traffic movement, alternating in direction till build-ups are dissipated. It is worthwhile to note what a build-up may comprise: one dilapidated AP bus, six or seven line Sumos (etymology of the name is unclear, for they do not adhere to any linear pattern when moving), three motorcycles, one Innova, one Maruti 800 and little else. On our way back home, many weeks later, it would take us a while to acclimatise back to the hordes even in Assam, and Calcutta would seemed like a suffocating Noah’s Ark, everyone stuffed in on a gangplank and hoping to make it out alive. The morning had been cold but with the sun shining today, it was getting warmer. We were moving fast, keeping a lookout for stray rocks on the side of the mountain for potential landslides. Suddenly we saw two bodies lying on the road ahead — a human and a canine. Oh my god, what…? The bodies then detached themselves from the road and got up looking disgruntled. Medusa had interrupted their naps on a sun-warmed tarmac. The highway in these parts was punctuated with bridges, so many that after sometime, boards simply said “Bridge”. Authorities must have run out of names to give and ribbons to cut. As we got closer to the border, a series of memorials, beginning in the Namti Plains, acted as milestones for the 1962 conflict. Watchtowers were manned by sole sentries on postings that last two and a half years; families of many cannot afford to come to meet them so far away. Signboards told us we were under surveillance, including the enemy’s. The Indian mobile signal disappeared and Chinese mobile signals came up with enticements of free internet. There is something in the air near the border, as a friend had said once. A hush, stirring of senses, foreboding, taut nerves, suspicious looks. We had to make an entry in a register before entering Kibithu, a small village that seemed to mostly serve the Army. One large store with a woman busily tending to needs of soap, shampoo, baking soda, toffees, Britannia cakes, Army scarves, cigarettes, lentils, rice, Maggi, matches, you name it. A restaurant next door did steady business of lal chaa before lunch. White walls of houses across the border looked slightly closer from here. One soldier started chatting with us and proudly told us he is stationed a few kilometres walk up on the mountain, where it’s cold and snowy. He was from Gujarat. Kaho, on the other side of the river and non-existent on Google Maps, is connected by another bridge some way back from Kibithu. It was even more isolated, with fewer people and one shop, proclaiming itself to be the first shop in India. The second shop, some distance back, proved to be more interesting. It was a kirana store attached to a room where loud music played. While we waited for our bread-omelette, we saw a stream of young, cheerful soldiers going in and out, some flirting with the smiling girl at the counter, some leaving in a hurry when a truck turned into what must be a camp behind. Just before, we had clambered on to our first wire and wood suspension bridge. The bridge had swung under my legs. We had walked on planks, some of which were not fixed and, horror of horrors, had been broken. I had clutched for dear life on to the rusted, twisted wires running along the side and stopped in the middle to take a breather. Ray of course had sauntered across like a local some time back. Muttering, I had crossed and clambered up the boulders, straight into an Army camp and lookout. The senior officer had offered us greetings and water and went back to work. The junior one had been a chatty Kathy, keeping us captive with questions on marital status, occupation, annual earnings, cars and thoughts on children till he had been sharply called back. We missed a turning on the way back to Walong and went deeper into nowhere for a few kilometres before correcting course. It was dusk when we reached the Dong Resort (neither in Dong nor a resort). A grinning woman behind the barred window in a room at one end of the property reduced the volume of the Bollywood songs blaring from the radio upon seeing us. She also happened to be the guide to take tourists up to the Dong village at 3am to see the first rays of the sun to hit India. Right. No, we will sleep in and look at them when it hits the resort, thank you very much. She shrugged and went back to her music after handing over the chips. As the dinner was being prepared, I sat in front of a bonfire, listening to the silence until it was shattered by a tempo traveller with a large family from Roing. They cheerfully sang songs and offered me cooked rice segments, flavoured with the bamboo tubes they had been cooked in and re-heated in the fire. The co-driver in the meanwhile was nowhere to be found. He had befriended off-duty Army folks and he confessed the next morning, allowed them to drive Medusa. After breakfast, we were on the road. I had given the key to Ray, knowing speed would be required to go back down and reach Roing, our next destination. It had taken us two-ish days to come up, but weather had cleared. He overtook everyone until we came upon the road construction site we had crossed on the way up. It was a long-ish stoppage and Ray got out to chat with fellow sufferers. Medusa was duly admired. I got out too, smiling sunnily, as I am wont to do on a sunny day. Some Arunachali men tittered at something an older man, with a smirk on his face, said in their language, his ornate dao indicating a higher standing. I was wearing a Uniqlo fleece, with foolish and lovely long ribbon ties on either side, which probably had caused the derision. I have no idea when I stopped looking unapproachable and formidable. Perhaps years have calmed me down, made me comfortable in my own skin and I no longer feel the insecurity that had made me look down arrogantly at people. I smile often, even when in groups or travelling, and no longer wonder if I give off serial killer vibes as people move away. I ignored them and hospitably took around a packet of biscuits bought from the bakery in Khupa. A thin, almost emaciated woman with a child stood a bit apart. She had come asking for water earlier for the child. When I went upto to her with the biscuits, the child grabbed the packet and to my utter astonishment, she sidled away without asking the boy to give it back. Oh well, she needed it more than me for sure, though peeved at not having even tasted one. When everyone scrambled back into their vehicles when it seemed the road would open, I saw her in the AP bus, looking straight ahead with such intensity it was clear she knew I was looking at her. Perhaps it is difficult to ask for something — food, money, help. Ray was back to overtaking everyone who had shot ahead, having taken his mission for the day seriously. And then reached another place where one could see people. This time, an errant boulder was the target of three JCBs. People had already pitched tents. One man shouted at no one in particular that the road will likely open tomorrow and drove away. We decided to hope and bake in the heat like all others. The man with the ornate dao was here again and I looked at him, and this time, he kept away. Perhaps because I stared at him with my erstwhile signature cold look, or then because he had no audience to impress. JCBs continued in the background to move around the boulder. Everyone watched it intensely for the next hour or so, collectively wishing it down the mountain side, till it obliged. The co-driver had been watching. We were again ahead in a flash, hurtling over rocks, flying over the terrain we had crawled up. We overtook the bus. We overtook bikes and small cars and an ambulance. We over took line sumos. One even tried to keep up, and then passengers in the backseat must have started hitting him. Ray gave a diabolical laugh. Everything was a green blur, as we kept up with the Lohit and, twisting and turning, reached NH13, spat out by the valley. Just in time for evening tea. No word had been spoken for the last couple of hours. Ray has always been an exceptional driver. Years have dulled his skill. Most of these days, he is a tad scrappy, and sometimes even reckless. But this drive was sublime, fast, and done with controlled aggression, perhaps the best I have experienced in the last 11 years of knowing him. And didn’t Medusa love it! He asked if I wanted to drive on the highway. I declined, saying the day belonged to him. The last couple of hours of the drive were gentle, the sun setting in front of us, on a surface that on occasion looked good enough to land a plane on, flanked by overgrown plants trying to reach across. We had completed the first valley and were making our way west on the Trans Arunachal Highway. The Lohit  Somewhere on the Hayuliang Road  At Khupa    Back on the Hayuliang Road   Near the border   Crossing a bridge towards Kaho    Back on NH13  Last edited by Aditya : 18th May 2022 at 09:58. Reason: Political reference, Rule #11 |

| |  (25)

Thanks (25)

Thanks

|

| The following 25 BHPians Thank Sonali Singh for this useful post: | Axe77, blackwasp, dailydriver, Dr.AD, GTO, gunin, g_sanjib, h0rnokplease, hmansari, Ironhide, JoseVijay, luvDriving, ph03n!x, Pyrotek, Researcher, Rigid Rotor, Roy.S, Samba, Sayan, Siddy_1998, sierrabravo98, somspaple, sridhar-v, SVK Rider, WhiteSierra |

| | #6 |

| BHPian Join Date: Jun 2021 Location: Bangalore

Posts: 28

Thanked: 470 Times

| Re: Arunachal: A Siren Call into the Unknown AT ROING, we checked into the Yatri Niwas. I had chosen the Mishmi Hut because it had a separate room that replicated the kitchen fire in traditional homes. With only pinewood available, it quickly became a cauldron of smoke. The market may be a safer bet, I told Ray. A leisurely stroll around the market soon proved to be no different than in any other part of the country, except everyone downed their shutters early. We were still not used to the timings the sun kept here. Next morning, Medusa got cleaned professionally and came out of her muddy disguise looking pretty as an orchid. The business of washing vehicles is currently booming in the state, possibly offering margins higher than cigarettes and tea, and greater demand too. While waiting at the workshop, I saw Donyi Polo flags in a few houses, a red sun emblem in the middle of a white background. Many tribes in central Arunachal continue to follow animist and nature worship practices, Donyi Polo (sun, moon) being the most recognisable of religious connections among them. There are indications of good ol’ Hinduism beginning to usurp its independent standing. A few Donyi Polo temples are now marked as Hindu temples, perhaps one of the few instances, for now, of the cultural hegemony agenda visible this far from Delhi. Anini had been dropped as a destination, what with rumours of long waits on account of road cutting. I was wondering whether we should have an easy day and simply make our way to Pasighat, when I chanced upon a lake with great reviews on Google Maps. Fifteen minutes later, we were looking, slightly disgruntled, at water surrounded by trees. Towns of all provenance are obsessed with nondescript lakes as a local or tourist attraction, higher up a hill or in a corner of a botanical garden or as a city-centre. Young and ageing couples, rowdy-sheeters and shrieking families, picnicking college girls, these man-made structures with mandatory accoutrements, such as boats, attract all and sundry. Dissatisfied with the morning, I said, onward ho to Mayudia Pass. Known as the lowest altitude thereabouts to see snow, I saw no harm in seeing what the hullabaloo was all about. We would get to experience a part of the Anini road too. In the days past and the days to come in the journey, this day terrified us the most. Within less than 5 km, we had stopped smiling at the crisp sunshine of a day. The road had shrunk to 1.25 lanes, at best, with mountain on one side and a sheer drop on the other. The highway to Kaho and Kibithu, with all its curves and parts of shot-to-hell infamy, had forests on both sides, milder in comparison to this deception one could easily have sped on, straight into the void in one last joyful acceleration. Even trucks were on 1st gear and line Sumos in 2nd. I went up to 3rd sometimes and would chicken out as soon as a hairpin bend came into sight. Plants on steroids were back. In fact, I am now convinced ferns could become trees, given freedom and fresh air. Understandably, a few botanist types were peering into plants. As we wound up, it started getting colder and quieter. There was no sound other than a few birds and the co-driver shouting instructions on how not to fly off the mountain. I had proudly overtaken a few trucks, likely because they wanted less annoyance on the road, and, they must have thought, who were they to stop others from realising their dreams of embracing oblivion. I had been looking at the fuel gauge. As Mayudia Pass had come up in our morning meandering, a mere 50 km away, we had ignored the cardinal rule of topping up. The calculated distance remaining in the tank was shrinking faster than our speed warranted. And I gasped when the low-fuel canister lit up on the dashboard. We were close to the Pass and there should be enough to take us down, I thought. Before I could process the sentence, the counter started blinking dashes instead of number. Less than a kilometre to go to the pass, fuel had run out. I drove, aghast, till there was enough space to park on the side and we got out. The closest petrol pumps were in Roing. Anini was still 170 kilometres away. And even if the vehicles we had passed were carrying extra fuel, why would they share? Over the next half hour or so, an Innova, empty oil tankers and a couple of line Sumos went past, as did the truck drivers, grinning at us, recognising our desperation; no, they had none spare. It had become bitterly cold. It was stunning too, the valley shrouded in mist. I could wait here and Ray could go down with the next vehicle to bring back some fuel up. Pleased with the positive outlook, I suggested we look yonder with mugs of tea. Ray declined. He had the look, that of Mathew McConaughey’s character at the beginning of the docking scene in Interstellar. Let’s not waste time and go down. We had passed a couple of villages where a litre or two might be available. I complied, hoping we would get stuck somewhere more hospitable. The 50 kilometres down were mostly in neutral to save on fuel, gears engaged only when breaking, curves negotiated with a flick of the wrist and a prayer. The Thar recognised something was up. The fuel gauge started showing “Distance to Empty: 5 kilometres” and then froze. We continued our descent, counting down the distance and cheering at each kilometre after 10 were left. When we reached the Roing petrol pump, the mileage was a record-worthy 24.4 km/l. Never, ever again will I forgo a top-up in the hills. A lunch calmed hearts down and we could ponder peaceably at the Boycott China poster (“Through bullet by army, through wallet by citizens”) before moving forward at a sedate pace.  Last edited by Sonali Singh : 16th May 2022 at 12:44. Reason: Revising travelogue |

| |  (31)

Thanks (31)

Thanks

|

| The following 31 BHPians Thank Sonali Singh for this useful post: | ABHI_1512, amol4184, Arreyosambha, AshwinRS, Axe77, Bibendum90949, blackwasp, dailydriver, Dr.AD, gadadhar, GTO, gunin, h0rnokplease, haisaikat, hmansari, Ironhide, JoseVijay, luvDriving, ph03n!x, Red Liner, Researcher, Rigid Rotor, Roy.S, Samba, Sayan, shipnil, Siddy_1998, sierrabravo98, somspaple, SS-Traveller, subie_socal |

| | #7 |

| BHPian Join Date: Jun 2021 Location: Bangalore

Posts: 28

Thanked: 470 Times

| Re: Arunachal: A Siren Call to the Unknown THE road to Pasighat on NH13 is peppered with bridges, over Dibang and over Sisseri and over another I now cannot find the name of. And finally over the Siang, into which the Lohit and the Dibang and many other not-insignificant rivers merge soon after Pasighat to become the Brahmaputra. We checked into TojoGojo homestay that evening, run by a Galo family, where we had a delicious local dinner. I began to realise food cooked at home in the state has no dairy, no oil, no sugar; turmeric and chillies the only spices used, bamboo shoot and dried or fermented fish added for flavour. We went to the market, and picked up some local sticky rice and dried red chillies. And Ray spent the rest of the evening reminiscing about a rafting trip he had come here for with friends and visiting old spots. He said not much has changed. At the time of checking out, we met the lady of the house, who said the homestay is named after her father-in-law. She is a teacher. Her daughter, Irik, who helps in the operations and had taken our booking, had gone off for the day. The photograph with her managed to include the family dog that, despite many trips between family’s quarters on the ground floor and our room on the first, could not decide whether he liked us or not. At the Tojo Gojo Homestay  Pasighat Bridge over the Brahmaputra  Last edited by Sonali Singh : 16th May 2022 at 13:21. Reason: Revising the travelogue |

| |  (26)

Thanks (26)

Thanks

|

| The following 26 BHPians Thank Sonali Singh for this useful post: | blackwasp, curiousElf, dailydriver, DogNDamsel12, Dr.AD, GTO, gunin, h0rnokplease, haisaikat, hmansari, Ironhide, JoseVijay, luvDriving, ph03n!x, Pyrotek, Red Liner, Researcher, Rigid Rotor, Roy.S, Samba, Siddy_1998, sierrabravo98, somspaple, subie_socal, Vishal.R, WhiteSierra |

| | #8 |

| BHPian Join Date: Jun 2021 Location: Bangalore

Posts: 28

Thanked: 470 Times

| Re: Arunachal: A Siren Call into the Unknown AT any place in Arunachal, one is a hop, a skip and a jump away from a forest. With 66,000 sq. km. of forests, 80% of the state is a forest. Forest Survey of India helpfully lists the types in the state: tropical wet evergreen, tropical semi evergreen, tropical moist deciduous, sub-tropical broad-leaved hill (which one was this?), sub-tropical pine, Himalayan moist temperate, Himalayan dry temperate, sub-alpine, and even moist alpine scrub and dry alpine scrub. Take your pick. Every region has a distinct look, and a river, all mercurial cousins with common facets but distinct personalities. On our way to the valley with Tuting next day, for instance, we knew exactly when the Siang had been left behind and the Yamne had become our companion. Women in galles, the traditional wrap-around skirt, carried conical cane baskets hanging by a strap on their heads, filled with wood, produce and what-nots. We passed villages and small farmlands along the hilly road. Our hope to find what a write-up had claimed to be one of the longest rope bridges in the state were dashed. There were too many. The two people we managed to find and ask had stared at us in confusion. Longest bridge? Desire for such a superlative is trivial in places where time passes slowly. The co-driver had decided Medusa needed a mini-workout. He swerved off the highway and aimed for the river bed. Down and down, and further down we went on what appeared to be pebbled tractor tracks. The distance to the river bank was quite an under-estimate but was soon covered. And there was a rope bridge, unsurprisingly, albeit not a super-sized one. Farming was evident in the flatter sections closer to the river, though, again, farmers were not. A lone fisherman was at work at a distance. The traditional basket fishing nets in the shallow waters were likely placed by him. Stealing large lemons from the short trees scattered around provided some excitement before we retraced our way back up. The rest of the drive was uneventful, except for the largest rainbow I have ever seen, one that stayed a long time before disappearing. We halted for the night at Yinkiong. A weekly fair was underway in spite of the rain. All manner of things required for domesticity are brought in by traders from states as far as Uttar Pradesh: underwear, jalebis, slippers, jackets, hammers and nails, cutlery, plastic buckets. People from villages around the town come to shop. Everyone jostles for space around wares spread on tarpaulin sheets. Only one stall on that day was run by a local family. It had two products: handcrafted daos with handles of mithun bone and long slats of polished teakwood, for the backstrap looms. Women still weave their own garments, I exclaimed with shock to Ray. Another hole-in-the-wall hotel, another local dinner, another cold night, another morning without a bath, another catch-up on the news that was an irrelevant cacophony in our sequestered existence. By now we should have been alert to inaccuracies on maps and lack of people to get directions from. But there always is a bridge too many, with local and actual names, to confound the best navigator. We lost an hour trying to find Byorung Bridge. It’s the longest steel cable suspension bridge in the country, over waters unmistakably of the Siang. We crossed over, straight into no signal zone. The road maps said we had to take was closed. We followed the only other option through a village to a fork. Was there more meandering remaining or this was the right turn to Tuting? A reassuring aspect of valley travel in Arunachal is one can travel only in two directions, the right or the wrong. And at some point, a signboard or a peripatetic villager will help correct course. The road to Tuting was like a mini version of our month-long journey. Road blockages; oranges exchanging hands; winding roads, often single-laned, flanked by dense forests; clouds in the clear, blue skies; a river sometimes close, sometimes far, always snow-green; tea breaks in the middle of nowhere; Army convoys; line sumos, spewing dust, people and luggage; many stretches with no evidence of humanity; waterfalls and small bridges, with a lunch hut at the half-way point; simple fare of rice-potato-greens with fresh un-named river fish or local chicken; small villages indicated by a few huts along the highway; signs stating we were approaching either a stretch of signal or no-signal; sparkling sun on the windshield, Medusa bouncing along, happy and loving it. A black and white bird, or rather, a relay of black and white birds, accompanied us, each swooping ahead close to the ground before disappearing into a bush from where another would pop out for the next section. The bewitching magic of the land was in its full, unblemished glory. By dusk, mountains had again become pale blue-grey washes against a greying sky, the occasional snow-tip no longer visible, and we rolled into Tuting. It was dark and the homestay on the map had been given out on rent. A puzzled look on the face of the shop owner next door indicated the government subsidy for homestay had been taken without feeling the compunction to have one running. The Circuit House was busy preparing for an MLA’s visit for inauguration of a community hall and could not accommodate stray tourists. Everyone had gone home, light emanating only from white LED bulbs hanging in small stores and restaurants. Oh, how I hate that dim light. We trudged towards the town’s only hotel, an ugly block of building painted green. I wondered if I should sleep in the car. But legs needed to be stretched after a long day and thoughts of pitching the tent was batted away in the cold. It was another day for the Set Up. The hotel was the only ugly part though. We went walking in the moonlight and chatted with a surprised shopkeeper. Some houses had colourful paper stars lit up like small beacons. We followed carollers in a residential part. They walked in a line, singing quietly, to a small white house with a garden. Everyone went in, continuing their singing, their voices reverberating with faith around that bright little room. After they stopped, we left and found another line of carollers, who went to a larger house this time, clearly owned by the local rich. A man, the owner of the house, looked out at us and walked over. We said we were tourists and he insisted we come in. The family was Roman Catholic and belonged to the Adi tribe. Carollers, mostly women and children, were standing in a ring and singing in the large garden. We sat around the fire inside, quickly becoming the curiosity of the evening for the men sitting around. Our host’s wife, dressed in an expensive-looking galle, ensured we got lal chaa. A visiting Naga missionary helped solve the mystery of why the KA car registration was being mistakenly assumed to be from Kerala (missionaries from Kerala abound in the region, making the state the most well-known among all down under). At dinner time, children came in first and sat in line on the floor. They were given small parcels covered by wild leaves that opened to reveal steamed rice and become plates. A chicken preparation was served alongside. We were tempted to take them up on their offer for dinner but, as we had already told the restaurant back in the hotel to prepare dinner, we declined and bid goodbye after thanking them. Morning could not come fast enough and I stepped out to a glorious sunrise in the mountains. Tuting was beautiful in daylight, dense with forest and dotted with Buddhist flags, especially as we moved towards the Nyingma Monastery. The older student-monks were preparing for exams, while the younger ones were playing in with a football. A white Ambassador was displayed in a locked room, with a glass bowl of fruits and white flowers and a photograph of a cheerful monk in front of it. A short drive away, a road lead to the banks of the river, full of tall, white prayer flags. We gave it a pass, as it seemed to be privately held, and went looking for the local wire and wood suspension bridge over a narrower section of the Siang. The air was cold and clear, the sun gentle. A girl stopped to pray at a small stone on the ground next to where we had parked Medusa. She skipped across the bridge with a nervous energy. She was helping women across with the heavy loads when she suddenly fell down to the floor of the bridge. One of her legs dangled through the planks, the river moving fast far below — a shocking tableau. Ray and the men he was talking to hurried across. Calls were made and a man came running from the other side. She had had an epileptic attack so we called her father, Ray told me. By the time the father and the daughter started moving towards their village, she had somewhat recovered and was walking, albeit with support. Our next stop, Aalo, and the best route to it was debated at the breakfast table in a dhaba. The owner and a couple of customers tried to convince us to go there straight from Tuting, taking the right fork down from Yinkiong, instead of the left that would end up being a circuitous route via Pasighat and NH13. Road acchhaa hai, they insisted. Having been on the road for many days, I could translate what “the road is good” means: the surface has been levelled, and even has a little black tar, and the stoppages in that area for road cutting aren’t too long, and why do you ask, don’t you have just the car for anything thrown at you? We would be starting our driving at 930 and Google Maps showed a good 13 hours for the 300+kilometres to Aalo. No way we are driving in the dark over clawed mountains with official sinkhole warnings, I told Ray, recalling the area around the wrong bridge in Yinkiong, which we would have to go over to get to Aalo. On the sensible route, we would cover the difficult stretch till Yinkiong in daylight after which the road to Pasighat was smooth and double-laned. Aalo could wait another day. The day was long, the drive another heroic effort by the co-driver. We collapsed onto a hotel bed — the homestay was available but didn’t have food at such short notice — and went off to sleep. A hotel with luxuries like hot showers and clean bedsheets was worth revisiting Pasighat. On the road between Pasighat and Yinkiong    On the Yamne river bed    Back on the road to Yinkiong  Yinkiong    The Siang    On the road to Tuting     Tuting       Last edited by Aditya : 18th May 2022 at 10:02. Reason: Rule #11 |

| |  (29)

Thanks (29)

Thanks

|

| The following 29 BHPians Thank Sonali Singh for this useful post: | anivy, Bibendum90949, blackwasp, dailydriver, DogNDamsel12, GTO, gunin, h0rnokplease, haisaikat, hmansari, Ironhide, JoseVijay, luvDriving, ph03n!x, Pyrotek, Red Liner, Researcher, Rigid Rotor, Roy.S, Samba, Sayan, shipnil, Siddy_1998, sierrabravo98, Sran, SS-Traveller, subie_socal, V_Gupta, WhiteSierra |

| | #9 |

| BHPian Join Date: Jun 2021 Location: Bangalore

Posts: 28

Thanked: 470 Times