News

Living in Ladakh for an entire season: Understanding people & region

With the Tibetan border a stone’s throw away, the internet is tightly regulated here.

BHPian Red Liner recently shared this with other enthusiasts.

Holding up a baby pashmina goat in a nomadic rebo tent in Changthang, Ladakh.

In 2022, I decided to move to Ladakh for an entire season. I rented a shared house to set up base. Thereafter I traveled around Changthang, which sits by the eastern periphery on a self-supported journey to really get to know the people and the region. Armed with a little book to learn bhoti (the ethnic language of Ladakh), I was off on my exploration.

This is my story.

With the Next Generation

Mid-semester, I taught entrepreneurship to the students in SECMOL. SECMOL is an alternative school for Ladakhi students who have “failed” the normal study system that is in place in India. We adopted a hands-on program rather than a lecture-based one. In this 3-month workshop intensive, students were first grouped according to the geographies they came from. Then over a series of group discussions, they ideated and created products that represented their geographical ethnicity using material from the campus.

A whiteboard to brainstorm

Students of SECMOL

While the students from Sham valley and Kargil painted artwork, those from the Changthang made a model of the Rebo tent, and another team presented bottled seabuckthorn and barley teas with handwritten labels. The key element here was the students developed products that fully represented their diverse ethnicity within Ladakh. While most tourists view Ladakh as one single homogenous region, this program brought to the fore the many nuances and cultural identities that constitute Ladakh as a whole.

One of the groups presenting their ideated products

Vanishing traditions in Changthang

Mid year, I took the opportunity to travel extensively into the Changthang region and spent a month living in and around the village of Koyul, having befriended the earlier Goba (bhoti for headman).

Koyul is a small village of about 25 families nestled between Demchok and Nyoma. Herding and farming are the primary occupations. There is no phone network. With the Tibetan border a stone’s throw away, the internet is tightly regulated here. The signal one receives is beamed from a central BSNL tower for a couple of hours a day at the most.

I spend my time strolling around the village making small conversations. Living amongst the community gave me time and access to foster relationships.

Getting to know the local villagers

One night I was invited to a nomadic wedding where I got a first hand opportunity to hear wedding singers and their bagston lu’s or wedding songs. A key part of the wedding rituals, songs are sung to welcome the bride and groom and passed down from one generation to the next in the form of an oral tradition. So important were they that the wedding itself was put off for days together because the only singer in the region was unable to make it down from Hanle on time. But the younger generation is increasingly rejecting these ritualistic roles, most of them embracing the job of a DJ instead, like one young man at this very wedding playing songs from youtube well into the night.

A vibrant Changpa wedding on the far border with Tibet late into the night

The lama at Koyul is about my age, and we befriended each other easily. He invited me to the summer mela near Chisum Le which takes place every year. I observed as villages from around the area came together for a day of rituals, horse racing, and friendly games with the Indian army.

Horsemen destroying evil omens at the summer mela near Chisum Le

These events were helpful, as the locals had seen me consistently over the past few weeks. I was now being accepted as a part of the community and began making friends.

Saving the Pastures

I meet with a Changpa in his Rebo, camped on the banks of the Indus near Demchok. Over tea he laments about how little he earned from selling the raw unprocessed wool to traders who would visit them. On prodding about why he sells unprocessed wool, he laughs, “But we don’t know how to make Pashmina products”.

He was unaware of the actual prices of shawls and sweaters made from pure pashmina in the market or elsewhere, and I dared not tell him. Back in Leh, I find that Looms of Ladakh have been taking the first steps towards training Ladakhi women on creating their own pashmina products, helping unlock value within the local ecosystem.

Tsering and her father are Changpa’s. They are feeding a newborn pashmina kid

"Most of our winter pastures are in the forward areas where the Chinese are now blocking us", he tells me as he points out to the distance across the Indus where he claims the Chinese troops visit regularly.

Large white structures stare back at us — these are Chinese cameras keeping a watch. Winter, he says, is an especially hard time since access to fresh grass and fodder is impossible. I discover Solar lambing sheds which have been piloted successfully across a few villages in Changthang since 2005. A simple passive solar-based greenhouse that proves helpful in both growing and stocking fodder in the harsh winters. They even keep the younger goats warm enough to survive these critical months. But why more of these haven’t found a place here is a mystery — especially since a major starvation resulting in widespread deaths of the Changthangi goats in 2013.

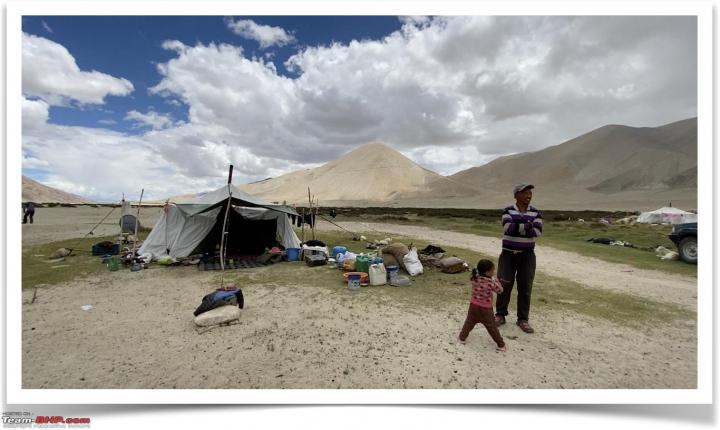

Changpa’s are nomadic pastoralists. This Rebo tent is their home for the next few months

The Changpa’s have also increasingly become over-reliant on pashmina.

Originally, there would be a good mix of sheep, yaks, and pashmina goats. Now most herders only keep the pashmina for obvious reasons. Without adequate yak dung, pastures are thinning out for lack of manure. Goats are also more earnest foragers contributing to the desertification of the pasturelands.

A lone pashmina grazes near camp. This pashmina was left behind to recover from injury

Last bus to Leh

More Changpas have been giving up the pastoral life of herding pashmina, and have instead gone on to work for the BRO and GREF, building roads at the borders.

The “achi” or sister whose home I am living in leaves every morning to catch the truck that takes her and many others to their day job at a road construction site nearby. "Yes, the work is backbreaking in the sun but I receive an assured daily income which I wouldn’t get if I was on my farm", she tells me. I find it difficult to argue with that. The silver lining is more locals are hired as opposed to bringing in migrant labor from other parts of the country.

A lone woman sits at a road construction site high in the Himalayas

Migration to Leh, especially Choglamsar is contributing to the disappearance of villages and culturally rich livelihoods like pastoralism. The key driver? Access to education. Primary schools are few and far between with just a handful of students and fewer teachers across Ladakh. At the primary school in Koyul, there are under 10 students in all and 2 teachers. The head teacher I meet tells me she was managing all the students and the school singlehandedly until another teacher was recently hired from the village of Mudh, which sits about a half day’s journey from here.

One of two teachers at a local primary school

There is an acute dearth of teachers who want to work in such stunning but desolate locations. The 17000 ft. Foundation has been doing stellar work in this area, helping local communities set up schools where there were none and beefing up existing ones with books, teacher training and computer labs. An audacious project of theirs? Geo mapping every single school across the remote Himalayas to help plan and track intervention, trying to stem this gargantuan issue at the root.

Back at the Rebo tent, Tsering’s dad tells me that she will likely not take after him to be a pastoralist. The money is too little for the hardship involved. She will need to move away for education, which he intends to provide for. "I didn’t study at all, and I was a herder from the time I remember. I don’t want my kids to take this path unless they choose to", he tells me.

But what happens to the pashmina and your way of life? Who takes it forward? He shrugs his shoulders as he looks out into the mountains. Somewhere out there is his herd of over a 100 goats grazing under the watchful eyes of his wife and sister, both of whom are shepherdess’. It’s a tough job.

Pashmina herds number in the hundreds

Continue reading Red Liner's experience in Ladakh for BHPian comments, insights and more information.

- Tags:

- Indian

- Member Content

- Ladakh

- Travelogue